A Secondary Injury Process

Not all brain damage occurs at the moment of trauma. Far from it. Brain damage occurring in that moment is considered a primary injury. It’s generally held, however, that the most significant damage in the cycle of traumatic brain injury occurs after the primary injury with the onset of secondary injury processes placed in motion by primary injuries. Excitotoxicity is one of several secondary injury processes and is a toxic condition in the brain caused by damage to brain neurons and to the blood-brain barrier. Excitotoxicity is a highly complex and destruction injury process, and as of now, no interventional protocols or treatment options exist to stop this damage process once it begins.

Chemical Imbalance in the Brain

Proper balance within the brain of the myriad of chemicals, hormones, neurotransmitters, and the like, is essential for optimal brain function, including mental and emotional health and well-being. “Homeostasis” is the medical term used to describe the “physiological tendency toward a relatively stable equilibrium between interdependent elements, especially as maintained be physiological processing.” In plain English, this means the human brain and body is naturally and constantly adjusting and readjusting on multiple levels, across all systems, to maintain a harmonious and stable environment. The brain innately knows that it, and the body generally, perform at optimal levels when all things are in proper balance.

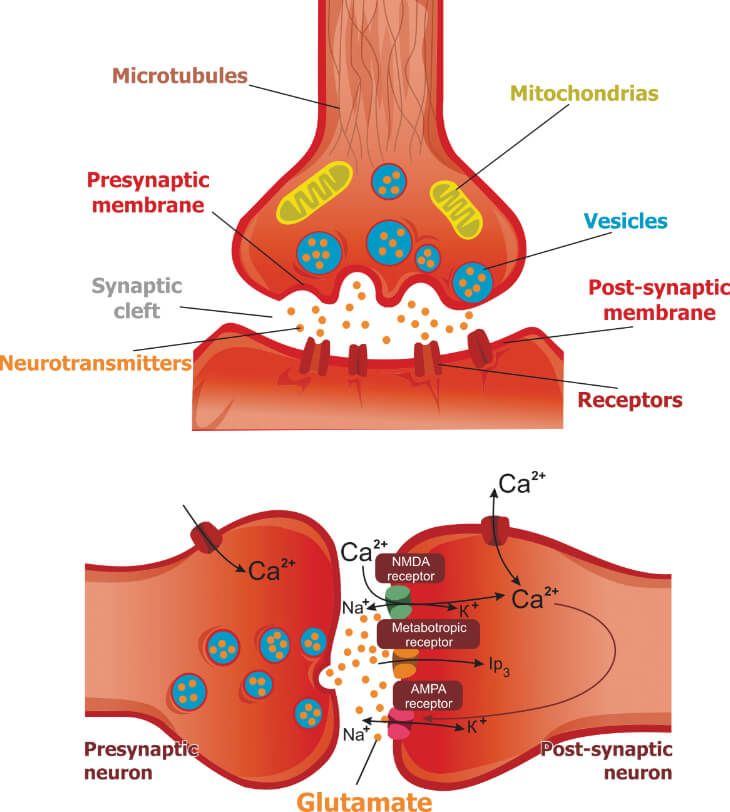

Excitotoxicity following brain trauma drastically alters brain balance by initiating a metabolic process within the traumatized brain that involves a series of chemical and nerve membrane reactions. These chemical reactions, which happen spontaneously, create a toxic environment that tragically leads to brain cell death (necrosis) on a potentially wide scale. This toxic environment is created by excess glutamate (a neurotransmitter) released into the brain following traumatic diffuse axonal injury (DAI). Here’s how it happens.

The “Glutamate Storm”

The neurotransmitter glutamate is prevalent in the brain, primarily stored inside brain neurons, and is essential to brain health. Glutamate, an amino acid, is the most abundant of all neurotransmitters and essential for sending brain messages/signals (neurotransmission) through and throughout the brain. The brain simply cannot function without it.

Each brain neuron contains massive amounts of glutamate (roughly 10,000 times greater than what exists outside the neuron), where it is safely stored and only released outside the neuron, by a healthy neuron, in small amounts when needed for neurotransmission. After a message is sent, any remaining glutamate outside the neuron not used up in sending the message is quickly reabsorbed by the neuron to maintain proper glutamate levels in the extracellular space (areas outside and surrounding brain neuron).

When a diffuse axonal injury occurs from trauma, the axons of countless brain neurons are compromised and/or broken. (see the section on Diffuse Axonal Injury for an explanation of the mechanism of injury). When this happens, the damage neurons react by dumping massive amounts of their stored glutamate into the extracellular space creating a sudden surge in glutamate levels and a toxic environment in the brain.

This surge is referred to as a “glutamate storm” which radiates out from the area of immediate neuron damage and destroys otherwise healthy neurons in nearby areas. And, when those neurons die, they too then release their own stored glutamate adding further fuel to the growing storm. This process results in a continuous metabolic cascade of neuron destruction. Depending on the severity of the initial trauma and the type of primary injury involved, this destructive process can start within hours of the trauma and continue for days thereafter.

Not surprisingly, excitotoxicity can cause serious, widespread brain damage. Medical science does not yet understand precisely why damaged cells dump their stored glutamate. The release is thought to some sort of cell defense mechanism. Obviously, if so, it’s a defensive response gone terrible wrong.

To learn more about excitotoxicity, see the featured article by Charlie Waters in The Center database: Excitotoxicity: A Secondary Injury in Traumatic Brain Damage.