Proving a Microscopic Injury

Most traumatic brain injuries fall under the “mild” classification, yet there is nothing mild about MTBI symptoms. They can be significantly disabling, chronic, and pose unique proof challenges to a brain injury lawyer. Simply stated, these cases can be difficult to prove.

What’s unique about an MTBI that makes it difficult to prove? What does it take to prove the existence of a MTBI? Why is it sometimes hard to prove the accident caused the MTBI? The answers to these questions, and similar others, can be found in the nature of the injury and in the limitations of medical science to confirm its very existence.

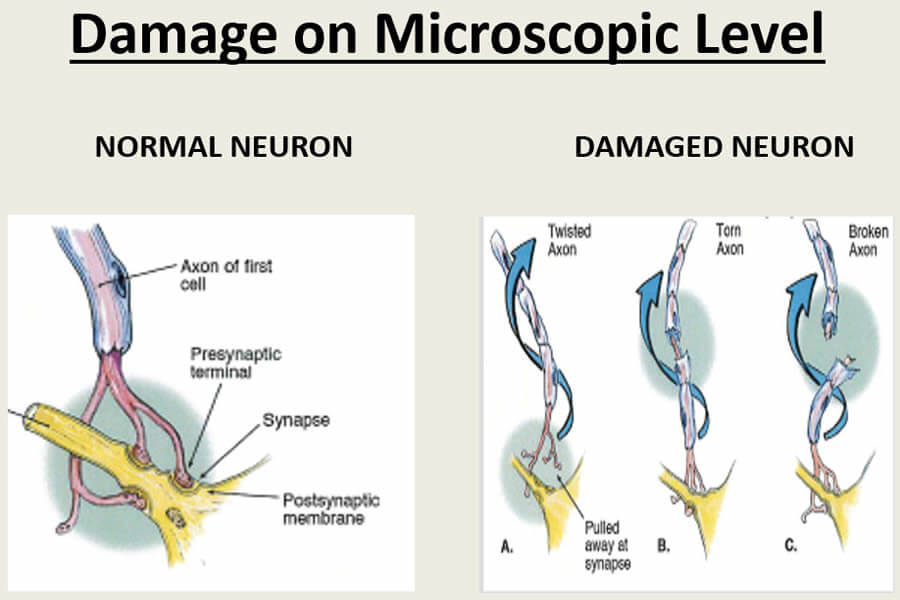

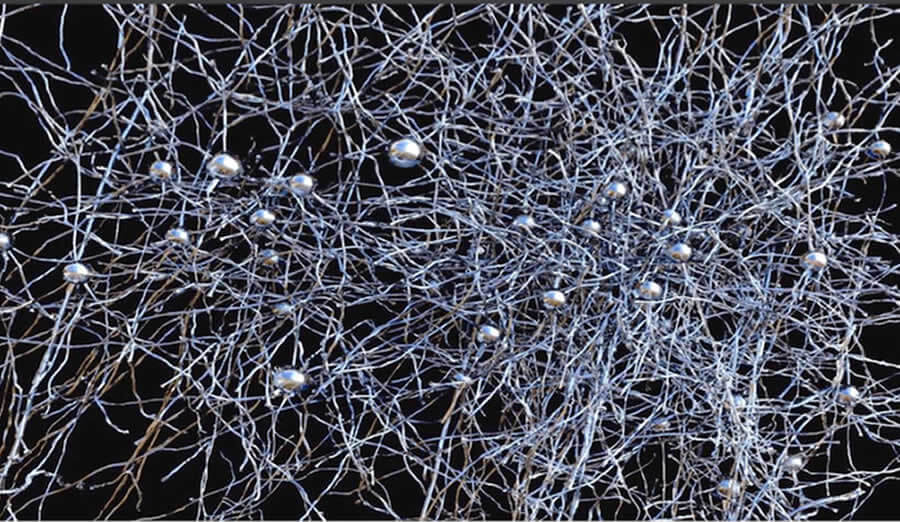

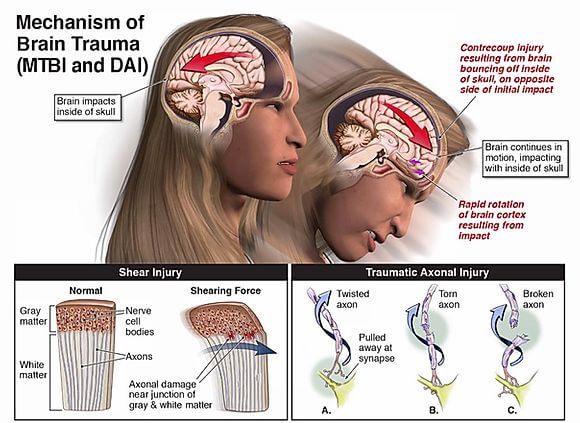

The brain functions by communicating through a vast network of interconnected neurons, as discussed in the Brain Anatomy section in this website.These neurons are microscopic in size, delicate in nature, and vulnerable to the acceleration/deceleration forces associated with traumatic events. When such forces are applied causing rapid backward and forward head motion and violent head rotation, the axons of brain neurons tend to shear, twist, stretch and break, causing injury over a widespread area of the brain.

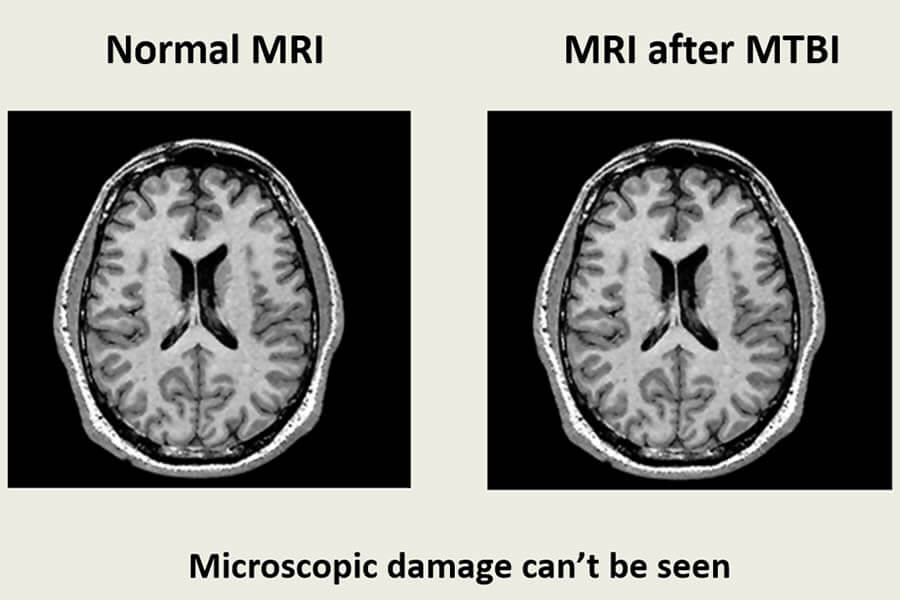

This is called diffuse axonal injury (DAI) and is at the root of all mild traumatic brain injuries. Proving DAI can be challenging because the damaged microscopic neurons and axons are not readily detectable through current imaging technology. In other words, axon damage like this can’t be seen. Yet, “absence of proof is not proof of absence.” We know these injuries are real, however, because after death the damage can be visualized through a microscope during autopsy.

Limitations of Imaging Technology

Various imaging technologies are available to help diagnose MTBIs, but each have their own limitations in detecting the full nature and extent of damage. Mostly, the limitations center around the inherent technological challenge of seeing and capturing an injury to something so small and not readily accessible. The current testing technologies include:

- CT scans (computed tomography scans) are normally used to evaluate patients in an emergency room for intracranial bleeding, brain swelling and skull fracture. They can show gross brain abnormalities but are not sophisticated enough to detect more subtle injuries and microscopic damage.

- MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) detect less obvious injuries and have 100,000 times the resolution of CT scans. They are generally used at later times if injury symptoms persist.

- SPECT scans (single-photon emission computerized tomography) measure the extent of blood flow in the brain by injecting a substance that can be tracked and mapped during the scanning procedure. This can indicate where normal blood flow has diminished which is evidence of areas of damage since they generally require and receive less blood.

- PET scans (positron emission tomography) create maps of glucose used in brain tissue. Functioning brain cells use glucose at a higher rate than damaged or dead cells.

- MEG scans (magneto encephalography) measure the magnetic fields produced by the brain’s electrical currents. It’s designed to record and evaluate the brain while functioning and then pinpoint the location of malfunctioning brain neurons.

- DTI scans (diffusion tensor imaging) are a form of resonance imaging that measures how water moves through the brain.

Proving a Microscopic Injury

MTBI symptoms vary from person to person and depend on the severity of the trauma. They include:

- headaches

- dizziness

- vertigo

- fatigue

- memory loss

- inability to retain and retrieve information

- slowed thought processes

- difficulty in multitasking

- spatial disorientation

- blurred vision

- hearing loss

- sound sensitivity

- ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- altered sense of taste and smell

- personality changes

- insomnia